Thailand–Cambodia Contest: Hard Power Gains, Noöpolitike Bites

- Geopolitics.Λsia

- Aug 27, 2025

- 13 min read

Our earlier warning made clear that Cambodia’s most potent weapon was never its firepower but its narrative. This remains the central asymmetry: Phnom Penh bends under economic pressure long before it breaks militarily, yet it cloaks weakness in the language of victimhood. The border war of July and its aftermath demonstrate how fragile this balance can become. The deep strike into Thai territory that killed civilians and destroyed hospitals, depots, and schools turned a symbolic quarrel into a breach of sovereignty. If such escalations were to be repeated, Thailand would be compelled to move beyond calibrated border closures and economic levers toward a limited military seizure, Poipet being the most obvious first target. The logic is straightforward: repeated aggression while claiming victimhood invites a demonstration that Cambodia’s gambit is futile against Thai C4ISR superiority and costly when paired with economic strangulation.

Yet the contest unfolding today is not decided by missiles alone. It is a competition fought simultaneously on the ground, in markets, and in parliaments abroad. Along the border, Thailand hedges between symbolic assertion and frozen restraint, facing pressure from domestic conservatives who demand bolder action. In Cambodia, economic contraction and a widening twin-deficit trap threaten the foundations of stability even as the regime doubles down on the rhetoric of lost territory. And in the skies, Thailand’s pursuit of the Gripen upgrade, and its longer-term hedging with the F-35, KF-21, or even domestic production, collides with Cambodia’s noöpolitike campaign to frame Sweden as an arms supplier to aggressors.

This essay traces those three dimensions in turn: first, the political and security dynamics on the border; second, the economic pressures and domestic climate inside Cambodia; and third, the modernization of Thailand’s air power and the contested politics of procurement. Taken together, they reveal a contest in which Thailand is steadily gaining leverage through hard power and economic weight, while Cambodia’s narrative warfare continues to bite deeply into the international framing of the conflict.

Political and Security Dynamics

The most recent developments along the Thai–Cambodian border reveal a contest where sovereignty, symbolism, and security remain deeply entangled, even after the guns have fallen silent. The five-day clash of late July, which left dozens dead and hundreds of thousands displaced, ended under an unconditional ceasefire brokered in Putrajaya on 28 July 2025 with the personal involvement of former U.S. president Donald Trump. The ceasefire has held for nearly a month, yet its fragility is evident. Both sides have resumed diplomatic sparring under ASEAN auspices, with Malaysia deploying observers to monitor compliance, but incidents on the ground continue to test the agreement.

At the center of the post-clash dispute is the Regional Border Committee (RBC), which convened in Sa Kaeo on 22 August. Cambodia accused Thailand of installing barbed wire inside contested territory, portraying it as a breach of the spirit of the ceasefire. Thai representatives rejected the charge outright, insisting the wire was placed strictly within sovereign Thai land as a defensive measure. For Bangkok, the move was both practical and symbolic: barbed wire serves to limit infiltration and reduce the risk of fresh landmine incidents, but it also broadcasts resolve at a time when the government faces mounting domestic pressure to demonstrate that it has not ceded ground.

![Thai Army Rangers conduct an operation to seize control of Phu Makua, as seen in a released video showcasing their tactical maneuvers in a forested area. [Source: Royal Thai Armed Forces]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/6072c3_d438dc85ea014b8fa42a0ce49ad31559~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_572,h_257,al_c,q_85,enc_avif,quality_auto/6072c3_d438dc85ea014b8fa42a0ce49ad31559~mv2.png)

The case of Ban Nong Chan, often referred to as Nong-Charn village, illustrates how these tensions translate into lived symbols. The village, situated in Sa Kaeo province, originated as a humanitarian refuge for Cambodians fleeing the Khmer Rouge. Over decades it expanded further into Thai territory, creating a long-running ambiguity that both sides now exploit. Thailand has consistently stressed that Nong-Charn lies within its territory under the terms of the 2000 Memorandum of Understanding, yet Cambodia has drawn upon the humanitarian legacy to justify its presence. Protests in the village, carried out by Cambodian civilians, were quickly amplified by Cambodian media and officials as evidence of community solidarity. Thai conservatives, by contrast, saw these demonstrations as a provocation and used them as leverage to pressure the army into reasserting control.

This dynamic has created a hedging strategy within the Thai military. On one hand, barbed-wire barriers and air patrols demonstrate resolve and reassure a domestic audience increasingly restless with what they perceive as government timidity. On the other hand, the army appears reluctant to escalate too far, aware that encroaching into areas of mixed habitation or creating new flashpoints could undermine its wider strategy of managing the dispute at a controlled pace. The army seems intent on freezing the situation in place, preferring a climate of stalemate that can be shifted later through negotiation under the General Border Committee or the Joint Boundary Commission.

Security incidents continue to feed tension. Sporadic drone flights and the discovery of personal mines near Thai positions have kept soldiers on alert. While no Thai personnel have been injured, the presence of explosives underscores the fragility of the border. In late July, the situation escalated into live clashes around the Ta Muen Thom temple area. Cambodian artillery fire and drone attacks prompted Thai retaliation, including F-16 strikes, in what became the most intense fighting since the Cold War era. Civilian infrastructure was struck, with hospitals, schools, and depots damaged, forcing the closure of border checkpoints and the recall of ambassadors.

Domestic politics have magnified the stakes. In Bangkok, thousands of demonstrators took to the streets demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra, accusing her of failing to defend Thai territory adequately. Conservative groups cast the government as weak and suggested that only military intervention, and perhaps a return to military rule, could safeguard national sovereignty. Across the border, Phnom Penh has encouraged nationalist demonstrations of its own. Tens of thousands of Cambodians joined rallies organized by the government, marching in support of the official stance and reinforcing the narrative of Cambodia as a victim of Thai aggression.

What emerges from these developments is a carefully managed but volatile stalemate. Thailand demonstrates its military superiority through selective force, but tempers that power with restraint and legalism, seeking to frame itself as the responsible actor committed to diplomacy. Cambodia, weaker in both firepower and economic resources, continues to draw strength from narrative politics, presenting its protests and symbolic gestures as evidence of resistance against a more powerful neighbor. The result is a contest where barbed wire and air strikes are as important as the framing of sovereignty and victimhood, and where each move on the ground is matched by a countermove in the political arena.

Cambodian Domestic Climate

The economic consequences of the border conflict are now unmistakable in Cambodia, where the twin pressures of external imbalance and fiscal shortfall are converging into what economists describe as a “twin deficit trap.” The immediate shock came from the sudden collapse of border trade with Thailand. In July 2025, the closure of all eighteen checkpoints drove bilateral commerce down by almost one hundred percent, leaving a monthly value of just 376 million baht. For Cambodia, whose economy depends on Thai fuel, consumer goods, and machinery imports, this was not a marginal setback but the removal of its cheapest and most reliable supply line. Replacement routes through Vietnam and Singapore proved far more expensive, adding transport and logistical costs that ripple through the economy.

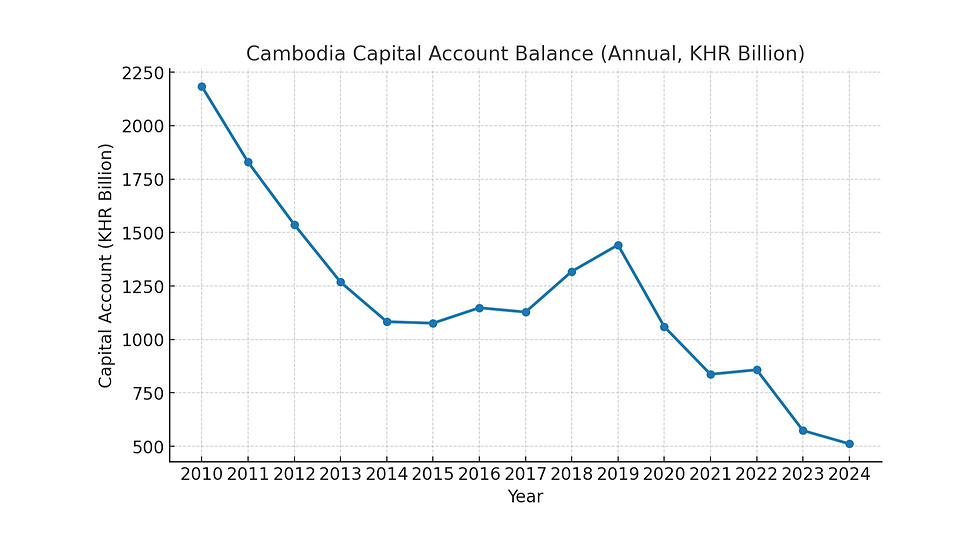

The collapse in cross-border trade has compounded an already fragile external position. Data from the National Bank of Cambodia show that the country’s trade balance, which recorded a surplus of over one trillion riel in 2020, had already eroded to just over 500 billion by 2024. By the first quarter of 2025, the surplus had nearly vanished, collapsing to a negligible thirty-three billion riel. Imports remain dominated by fuel, machinery, and food staples, while exports such as garments, agricultural products, and tourism services have stagnated under U.S. tariff measures, a global slowdown, and now the reputational damage of open conflict. The goods deficit in the first quarter alone reached over five trillion riel, more than double the shortfall a year earlier.

At the same time, Cambodia’s capital account has steadily weakened. The flow of donor support and concessional transfers that once helped cushion external deficits has shrunk since 2019, falling from more than one trillion riel to barely half that by 2024. This reduction in grant-type inflows leaves Phnom Penh increasingly dependent on foreign direct investment and external borrowing to cover its current account gap. War risk, however, makes both sources more volatile. If foreign investors hesitate or lenders demand higher risk premiums, the National Bank will have little choice but to draw down reserves or allow the riel to depreciate more steeply. Already, models suggest depreciation pressures of fifteen to twenty percent over the coming year unless external financing can be secured. Such a slide would import inflation directly, raising the cost of fuel and food and driving consumer prices toward double-digit levels.

The fiscal side is no less alarming. Customs receipts have collapsed alongside border closures, stripping away a vital source of revenue. At the same time, government spending has risen to cover military operations, security deployments, and subsidies for expensive sea- and air-borne fuel imports. The result is a widening fiscal deficit, projected at five to six percent of GDP if hostilities continue, financed by new debt or arrears in government obligations. The banking sector, meanwhile, is showing early signs of strain. Small and medium-sized enterprises face working-capital shortages, non-performing loans are expected to rise, and banks are adopting more cautious lending practices. Cambodia’s high level of dollarization provides some cushion, but it also limits the scope for monetary policy responses.

Our simulations make the trade-offs clear. If the war continues and only partial trade substitution is achieved, Cambodia’s GDP will remain six to ten percent below its pre-war level for at least a year, with inflation in the high single or low double digits and reserves rapidly depleted. By contrast, if hostilities cease and controlled trade corridors are reopened, the contraction could be limited to two to four percent, with inflationary pressures easing and deficits narrowing as revenues return. From a purely economic standpoint, the logic of de-escalation is overwhelming. Yet politics has rarely yielded to economics in Phnom Penh.

For now, the regime remains entrenched, maintaining its grip on political institutions despite economic pain. But the war has sharpened a sensitive nerve in Cambodian society: the perception of territorial loss. Nationalist discourse portrays Thailand as not only strangling the economy but also erasing Cambodia’s historical claims. This narrative has energized protests and state-sponsored rallies, but it also risks becoming a double-edged sword. As living standards deteriorate and shortages mount, the claim of victimhood may lose credibility, leaving the regime exposed to criticism that it has sacrificed the economy for symbolic ground. The economy, in other words, bends under pressure long before it breaks—but when it bends too far, even the strongest narratives begin to fracture.

Military Modernization and Procurement

Thailand’s decision to proceed with a new batch of Saab Gripen E/F fighters marks the most consequential modernization step for the Royal Thai Air Force in more than a decade. The cabinet’s approval of four aircraft, budgeted at nearly twenty billion baht, is only the first phase of a long-term plan that envisions up to twenty Gripens by the mid-2030s. In strategic terms, this is less a mere acquisition than the backbone of a system-of-systems approach: Gripens are designed to integrate seamlessly with Thailand’s existing Erieye airborne early warning platforms, its Link-T command and control architecture, and a wider push toward network-centric deterrence.

For Bangkok, the Gripen expansion fills the looming gap left by the retirement of its aging F-16s, many of which date from the 1980s. By the 2030s, a mixed fleet of twenty Gripens supported by Erieye radar would give the air force a robust defensive core against regional competitors. At the same time, Thailand has not abandoned its ambition for stealth capability. The United States turned down a request for F-35s in 2023, citing concerns over readiness and maintenance ecosystems, but officials in Bangkok continue to see the F-35 as a logical complement for Gripen. A two-tiered structure—Gripen as a networked, affordable workhorse, and a smaller F-35 squadron as a “first day of war” strike asset—remains a plausible trajectory by the late 2030s.

The Swedish decision to approve the sale was not automatic. Saab’s exports fall under strict oversight by the Inspectorate of Strategic Products (ISP), and arms sales are politically contentious in Stockholm. The Moderate-led government, backed by Christian Democrats, Liberals, and Sweden Democrats, frames Saab as both a strategic necessity and an industrial pillar. Thousands of jobs in Linköping, NATO credibility, and technological sovereignty make the Gripen program difficult to oppose. The Greens, however, have long resisted arms sales to states in conflict or under authoritarian rule, and Cambodia’s lobbying efforts have deliberately sought to activate this political flank.

Recent Swedish press illustrates the vulnerability. In August 2025, Green Party MPs publicly called for a freeze on arms exports to Thailand, citing the use of Gripens in combat against Cambodian positions as evidence that Sweden was arming authoritarian regimes. They argued that the democracy criteria introduced in 2018 were being hollowed out by exceptions, and that the Thai deal epitomized this failure. While the current parliamentary arithmetic shields Saab, a future coalition of Social Democrats and Greens could well delay or suspend deliveries, especially if the border conflict remains active and civilian casualties are highlighted in international forums. Cambodia’s campaign, therefore, is not reckless but calculated: it may not derail the first tranche of Gripens, but it could slow or complicate later acquisitions, or at least raise reputational costs for Saab globally.

Thailand is aware of these vulnerabilities and hedges accordingly. Beyond Gripen, the air force has been courted by South Korea’s KF-21 Boramae program, which is moving into serial production and may be available for export by the early 2030s. The KF-21, larger and longer-ranged than the Gripen, could serve as a complementary platform, especially if political turbulence in Sweden casts doubt on future deliveries. U.S. export controls over the GE F414 engine, however, mean that Washington would still have a veto over any Thai purchase. The United States itself remains a future supplier: once relations stabilize, Thailand could return to the F-35 request, or pursue a mixed fleet of Gripen, KF-21, and eventually stealth aircraft.

Equally significant is Thailand’s use of offset policy to prepare for a more independent future. The Gripen deal includes provisions for technology transfer, training, and local supply chain integration. Already, Thailand has built capacity for depot-level maintenance, Erieye upgrades, and sovereign control of its Link-T communications system. Over the next two decades, this could evolve into limited component manufacturing, avionics integration, and even license assembly of future fighters—mirroring Brazil’s experience with the Gripen program. Although a fully indigenous Thai fighter remains a distant prospect, the steady expansion of domestic capacity suggests that Bangkok views the Gripen program as more than procurement. It is also an industrial ladder, a means of climbing from maintenance to assembly, and eventually to co-development of future systems, including unmanned loyal wingmen and advanced C4ISR networks.

For Cambodia, this trajectory underscores its strategic asymmetry. Even if lobbying in Europe raises political noise, Thailand’s modernization path is resilient. The Gripen program is anchored by industrial offsets and domestic political support in Sweden, and hedging with KF-21 or F-35 reduces vulnerability to any single supplier. Cambodia’s campaign may not prevent Bangkok from acquiring new jets, but it does impose costs—delays, uncertainty, and reputational risks that Thailand must factor into its long-term planning. In that sense, the contest is no longer just about airframes on the tarmac. It is about the credibility of suppliers, the resilience of political coalitions, and the ability of small states to exploit narrative leverage against superior military power.

Update: The Second Army Region has reported that three Thai soldiers were injured by a landmine near the right side of Ta Kwai temple. All have been evacuated and transferred to hospital for treatment.

Comments